Security for Seniors

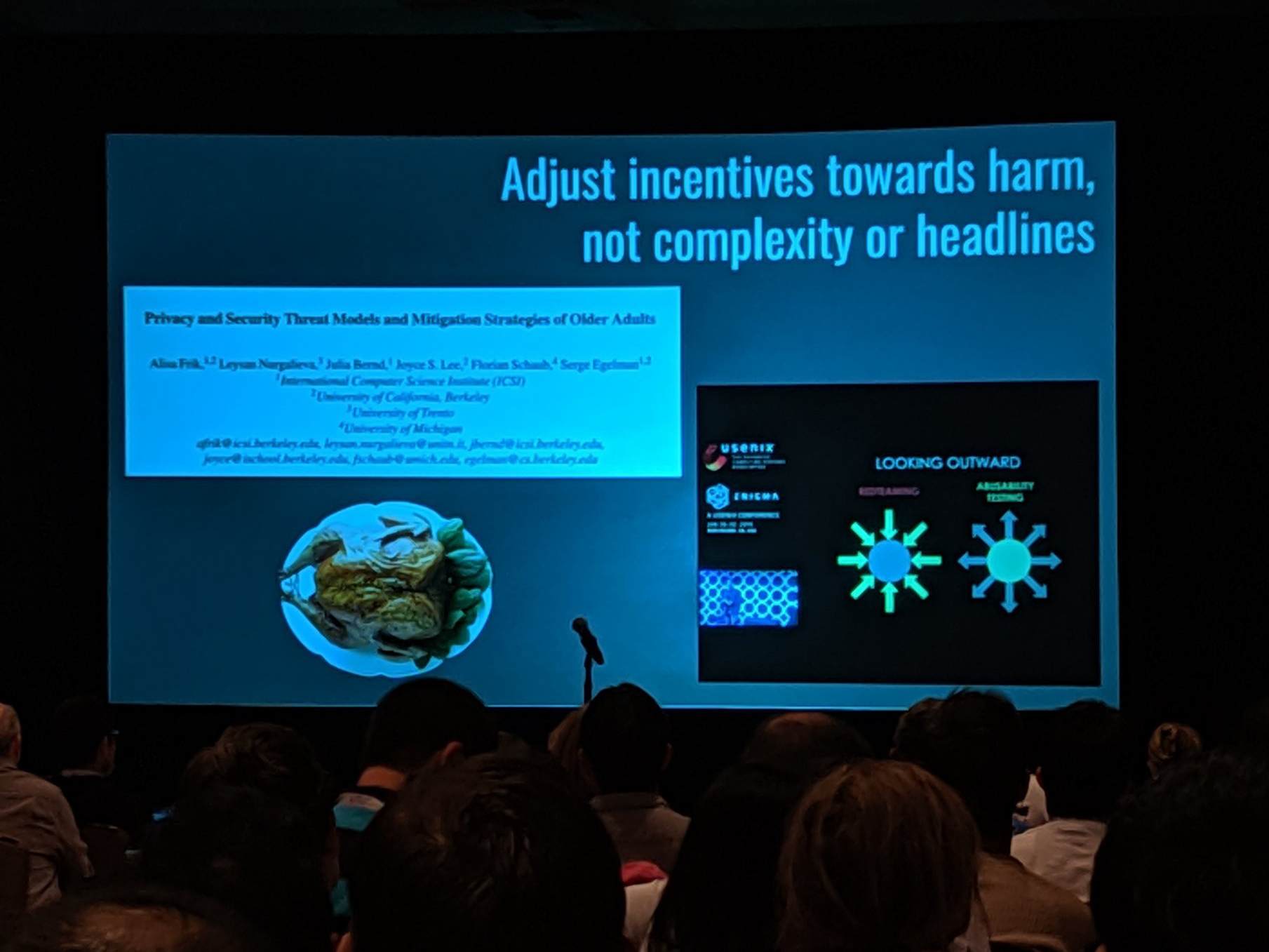

I worked with a team to conduct semi-structured interviews with 46 older adults (65+ years). In coding and analyzing these transcripts, we identified a complex range of privacy and security needs specific to this population, along with common threat models, misconceptions, and mitigation strategies. Supported by a research grant from the Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity, the results were published and presented at the 2019 Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS). The paper was also highlighted during the USENIX keynote by Alex Stamos, chief information security officer at Facebook.

Contributions

Literature Review

Participant Recruitment

Contextual Interviewing

Qualitative Coding & Analysis

Collaborators

Alisa Frik

Leysan Nurgalieva

Julia Bernd

Florian Schaub

Serge Egelman

Background

Older adults (aged 65+) are emergent users of smart systems, especially in health care. However, these technologies are often not designed for older users; moreover, they can pose serious privacy and security concerns due to their novelty, complexity, and propensity to collect vast amounts of sensitive information. Due to infrequent use, limited technical knowledge, and age-related declines in ability, older adults can be particularly vulnerable to privacy and security risks.

Overview

To study older adults’ privacy and security attitudes, we conducted 1–1.5 hour semi-structured interviews. In these conversations, we discussed: (1) current technology use, (2) privacy- and security-related concerns and (3) user management strategies. Participants were recruited via nursing homes, senior centers, and organizations for retired people in the San Francisco Bay Area.

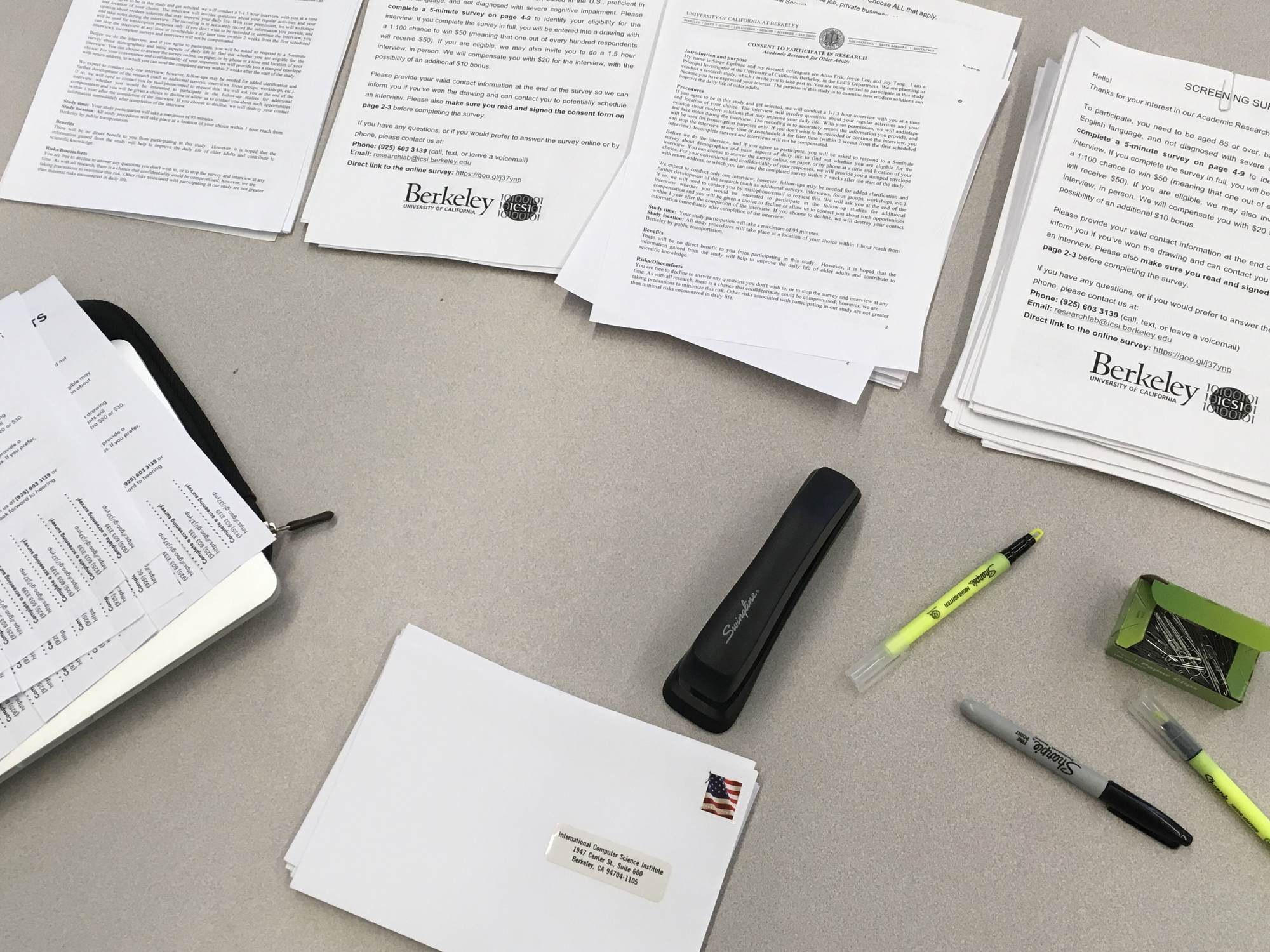

We screened potential participants using surveys in several formats — online, phone, paper, and in person — but excluded individuals with serious cognitive impairments and limited English comprehension. With approval from the Institutional Review Board, we conducted interviews from May to June 2018; interviews were conducted with 46 participants in person, at their residences or public senior centers (their choice). Sessions concluded with exit surveys about participants’ individual characteristics, either self-administered or by the researcher (also their choice).

The interviews were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, then coded. Three coders iteratively developed a codebook by independently coding subsets of transcripts and jointly resolving conflicting codes. To maximize the value of thematic analysis, 4 researchers used a holistic coding approach, in which at least 2 coders per interview applied open coding to entire interviews, independently selecting excerpts to annotate. All 4 coders then resolved disagreements at the interview level (so that at least 3 out of 4 agreed).

︎A participant examines some graphics used as probes to understand potential technologies and their uses.

︎Participants were recruited through tear-off flyers and in-person announcements at senior centers. Paper screeners included self-sealed envelopes for return to the researchers.

︎One participant, an avid Fitbit and iPhone user, fills out the paper exit survey.

Outcomes

We identified a range of complex privacy and security behaviors specific to this population – from use of public and secondhand devices to caregiving responsibilities both for themselves and others. Our work adds depth to current models of how older adults’ limited technical knowledge and age-related ability declines amplify vulnerability to certain risks; we found that health, living situation, and finances play a notable role as well.

We also identified usability issues with current protections, learning and troubleshooting approaches, and misconceptions regarding security and privacy. We found that older adults often struggle to mitigate known and unknown risks — and that managing them frequently consists of limiting or avoiding technology use. Building on the preferences of older adults, we conclude by offering privacy- and security-enhancing recommendations for product developers and for educational programs.

For more information, see the resulting SOUPS paper and presentation.

︎One blind participant shares her digital audiobook player as a technology she frequently uses.

︎Another participant shares her Jitterbug phone. She described frequently forgetting to carry it with her – in this instance, leaving it in the trunk of her car.

︎ The paper was highlighted during the 2019 USENIX keynote by Alex Stamos, chief information security officer at Facebook.

Takeaways

The project was a valuable exercise in recruiting participants of a somewhat difficult-to-reach population. It also highlighted the need to use a variety of approaches — i.e. online, phone, paper, and in person — to administer screeners and surveys for the population of study. Lastly, given that the interviews required the discussion of sensitive topics, it helped to develop skills in establishing rapport and gaining trust.