Reimagining Mobility

Over the course of three months, I led three rounds of research to reimagine the future of accessible, autonomous transportation for the Ford Research & Innovation Center. This included 12 interviews to understand various stakeholder perspectives as well as eight generative research sessions to iterate and co-create a service design prototype.

Contributions

Market Research

Interviewing

Synthesis & Ideation

Usability Testing

Project Management

Collaborators

Corten Singer

Nancy Yang

Takara Satone

Reece Clark

Background

Examining extreme users can lead to solutions that are not only more inclusive, but also better for everyone. Consider curb cuts: despite being initially designed to comply with the American Disabilities Act, one study that found nine out of ten “unencumbered pedestrians” go out of their way to use a curb cut. Furthermore, America is aging, and 40 million Americans currently live with a disability, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2015 American Community Survey. Unsurprisingly, Americans aged 65+ years make up the majority of this population, which is projected to double by 2050.

Overview

Looking beyond cars, the Ford Research & Innovation Center is taking on a user-centered, systems-level approach to designing for mobility. I had the opportunity to conduct design research for Ford through the Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation. Over the course of three months, I worked with an interdisciplinary team to reimagine what the future of mobility might look like in the next 10 to 15 years, focusing on the following challenges:

- How might we incorporate accessibility in the design of future transport?

- How might we design solutions that can benefit a broader population as well?

How might we incorporate accessibility in the design of future transport?

Market research

We began our process with analysis of secondary data, to better understand the current ecosystem. Although the number of wheelchair users is predicted to grow, it is a deeply underserved market. From crutches and canes to walkers and wheelchairs, mobility-enhancing products exist but are standard issue – there is a lack of innovation in the space. This in spite of the fact that cars and wheelchairs can be comparable in cost: the price of a power wheelchair can go as high as $30,000, according to the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Public transit services meet accessibility standards, but only because it is required by law. While legislation helps advocacy groups and nonprofit organizations improve access to assistive services, they are rarely well funded and still require extra work from mobility-impaired individuals. In the private sector, ride sharing services often don’t have amenities for wheelchairs; however, large technology companies are pioneering initiatives – like Microsoft NeXT and Apple Accessibility – to improve access for the mobility impaired. Although they have deep pockets and wide reach, going to market remains a slow process due to liability risks.

︎ Our secondary research identified the mobility impaired as a growing but underserved market.

︎Emergent themes from analyzing the current experience ecosystem include time, expenses, regulation, community, and public awareness.

In-depth interviews

Informed by market research, we proceeded to conduct 12 in-depth interviews with relevant stakeholders. We spoke to a group diverse in age, ethnicity, and degree of impairment: this included nine wheelchair users and three able-bodied caregivers for patients in wheelchairs (one of whom was also a patient’s spouse). A few key insights emerged:

- Society is inattentive to people in wheelchairs, both in physical space and in regard to resource allocation. “Every day I am yelling at a driver for pulling some boneheaded move,” said one interviewee. Another participant shared a story about waiting for the bus for over an hour: “You can only fit so many chairs in there, at most two at a time,” he explained. “If it’s already full, you just have to wait for the next bus.”

- Paradoxically, wheelchairs both enable greater mobility and reinforce limitations in regard to users’ sense of self. Despite the sticker price, hardware is limited in choice, lacking features of empowerment such as safety lights, thicker wheels, and longer battery life. “To not be at the mercy of anyone else would be amazing,” said one wheelchair user. “I haven’t been in a car alone for over 15 years.”

︎A sampling of the stakeholders interviewed, both in person and remotely.

︎A sampling of the stakeholders interviewed, both in person and remotely.How might we design solutions that can benefit a broader population as well?

Participatory design

To engage relevant stakeholders in participatory design, we asked caregivers of wheelchair patients to create collages responding to the prompt, “What do you hope the future of mobility will look like?” Participants described their collages with words like “helpful,” “comfortable,” “fast,” and “convenient.” We additionally asked wheelchair users to write love letters to idealized mobility products and services. These letters introduced new concepts of flexibility and personalization – and emphasized the emotional weight of mobility. One participant wrote, “Words cannot express how much you mean to me because without you, I’d go nowhere in my life.”

︎Love letters to idealized mobility products and services, written by wheelchair users.

Furthermore, I rode around the Berkeley campus in a wheelchair myself, as a “walk-a-mile” exercise. I was struck by a visceral claustrophobia in halls and doorways; in a wheelchair, it was evident that the world was not designed for me. I had to consult building maps to identify accessible exits, and ask for help when accessible door buttons were broken. Anything but the smoothest sidewalks felt terrifying; I was constantly worried about tipping over. I also understood how interviewees described feeling invisible firsthand. Sitting far below everyone else’s eye-level, I would find myself unknowingly unacknowledged.

︎Riding a wheelchair around the Berkeley campus as an empathy-building exercise.

Ideation, sketching, and storyboarding

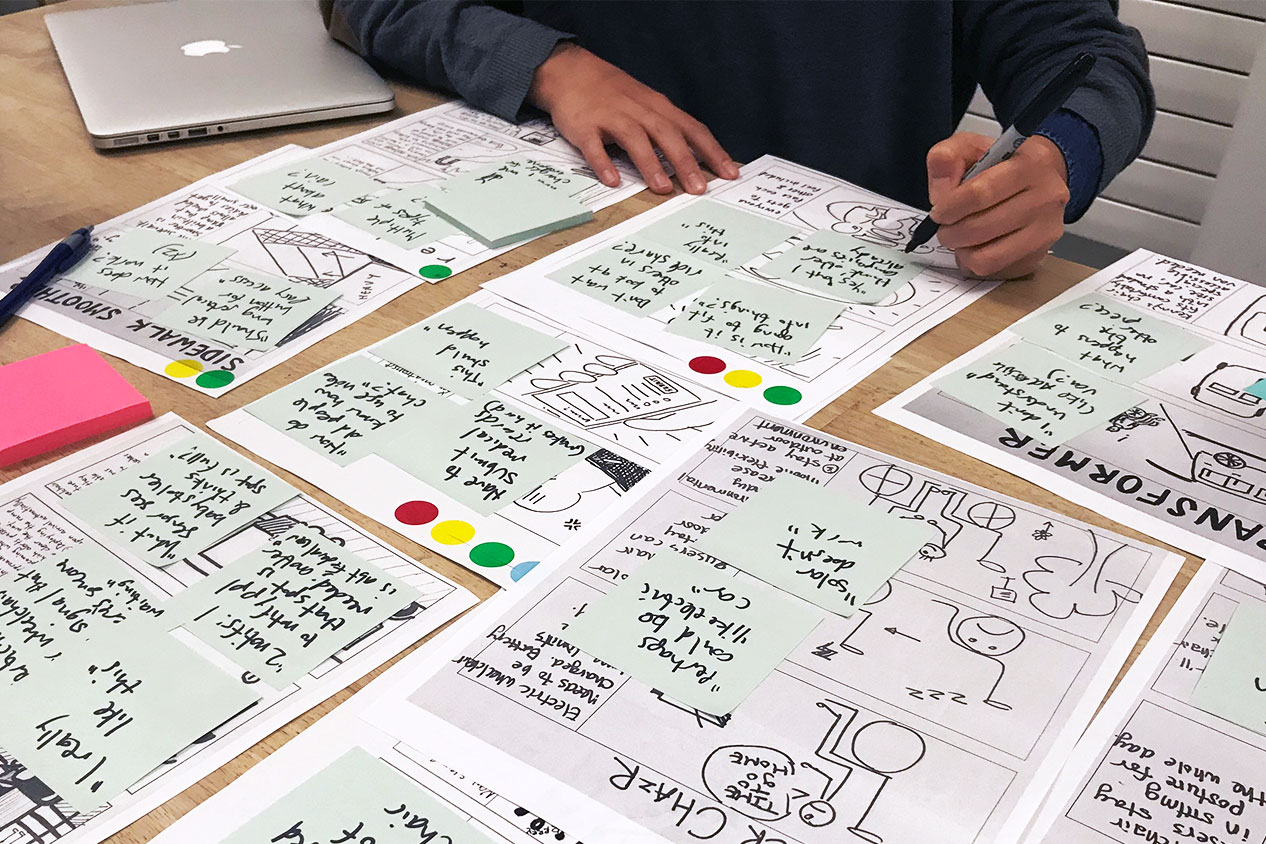

Equipped with research insights, we used the Luma Institute’s Creative Matrix to identify possible solutions. After a democratic discussion, we went on to create storyboards for our 10 most promising ideas. To design solutions with crossover potential – meaning, not just for wheelchair users – we used a “speed dating” approach among non-wheelchair users to get feedback on our storyboards. Even on more wildcard concepts, like a public wheelchair charging station, we heard helpful ways to their broaden appeal, such as, “Maybe add chargers for other devices (like phones),” and “Everybody’s battery dies. It would be good to have this, especially at night when you don’t want a dead phone.”

Based on participants’ top votes and client feedback, we developed a prototype of a hybrid service incorporating a few of the concepts. This prototype was guided by 2 design principles: community – making transit a time to promote connection with others – as well as inclusivity, or normalizing accessible enhancements that enable mobility for everyone.

︎Evaluating feedback from "speed dating" storyboard concepts.

Outcomes

Our research culminated with Alula, a transit solution named after the bird's "thumb," which enables it to fly. In the context of autonomous public transit, there is an absence of drivers who make bus rides accessible for people living with mobility impairments: drivers both deploy the ramp and advocate for wheelchair users. With Alula, we consider an end-to-end transportation system that remains accessible, even in the absence of bus drivers. Key features are centered around our design principles:

Community

- Parklet bus stops. Waiting is more pleasant when bus stops are community gathering areas.

- Passenger notifications. Alula promotes social accountability by notifying passengers to make room for people that need extra space.

- Personalized messaging. Based on user input into a mobile application and GPS location, the passenger receives personalized reminders when it’s time to disembark – enabling conversation and peace of mind that they won’t miss their stop.

Inclusivity

-

Modular bus seats. Flexible seating permits passengers to make room for people who are boarding the bus.

-

Automatic ramps. Deploying the bus ramp at every stop prevents “other”-ing those with mobility impairments, making accessibility the norm.

- Priority seating requests. With a simple photo upload, all passengers can apply for priority seating to accommodate both long-term disabilities and temporary requests. Image detection enables immediate approval to support those needing extra space, while a long-term request goes through a more thorough human review.

︎Once the user inputs a destination, the app suggests nearby parklet bus stops.

︎Existing passengers are notified of priority seating requests and can make room with modular seats.

︎Existing passengers are notified of priority seating requests and can make room with modular seats.

︎Ramps are automatically deployed at every stop, making accessibility the norm.

︎Personalized messaging and device charging promote passenger peace of mind.

Takeaways

Designing an end-to-end transportation experience was educational, leading me to think of possible improvements in future work. I learned the importance of communicating how the whole system works all together: for instance, attempts to get feedback through UserTesting.com led to confusion among participants, as the app alone didn’t fully communicate the service. This process additionally provided the valuable experience of working with a client, emphasizing the importance of storytelling to communicate an overall solution.