Life in a Minute

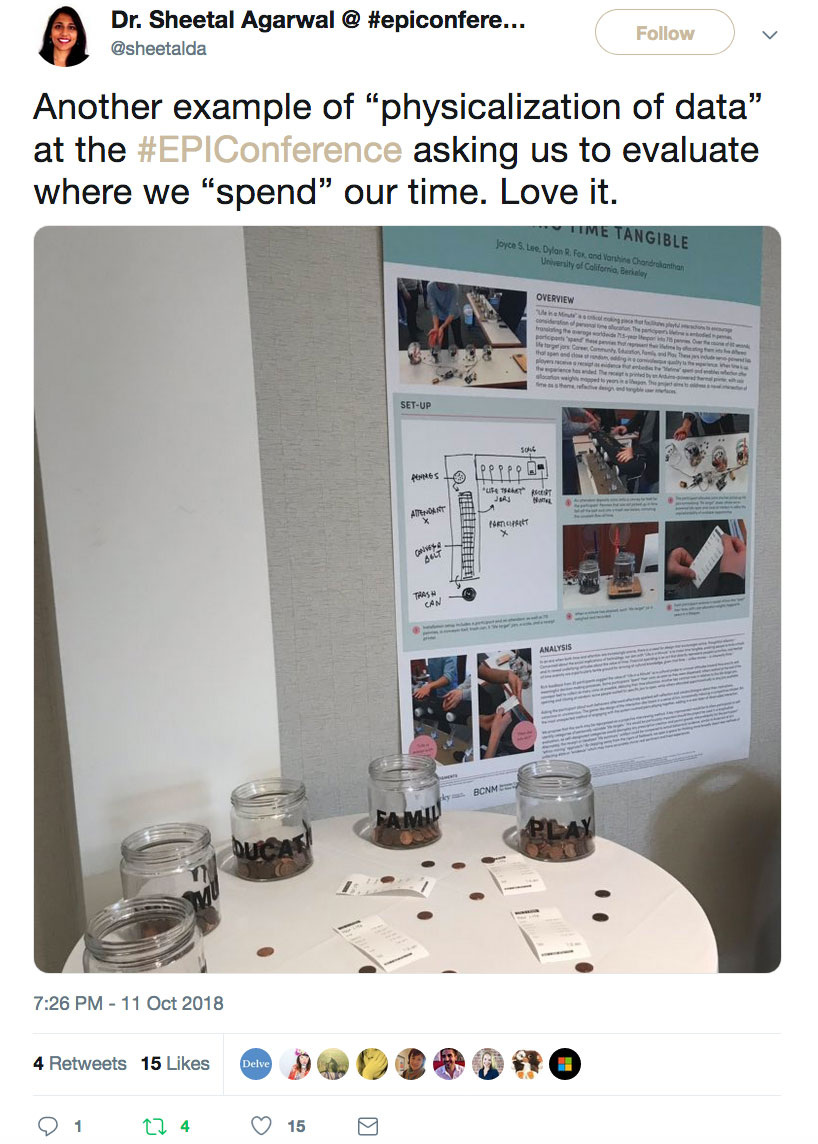

“Life in a Minute” is a critical making installation that facilitates playful, tangible interactions to encourage reflection on personal time allocation. With support from the Berkeley School of Information and the Berkeley Center for New Media, the project was exhibited in the gallery of the 2018 Ethnographic Praxis In Industry Conference (EPIC).

Contributions

Hardware Prototyping

Interaction Design

Observation

Literature Review

Collaborators

Dylan Fox

Varshine Chandrakanthan

Mentors

Kimiko Ryokai

Noura Howell

Background

In an era when both time and attention are increasingly scarce, there is a need for design that encourages active, thoughtful reflection. Concerned about the social implications of technology, our aim with “Life in a Minute” was to make time tangible, probing people to think critically about the value of time and to reveal underlying attitudes.

The metaphor of financial spending is an act that directly represents people’s priorities: we hypothesized that feelings of time scarcity are a particularly fertile ground for arriving at cultural knowledge, given that time is inherently finite. This project thus addresses a novel intersection of time as a theme, reflective design, and tangible user interfaces.

Overview

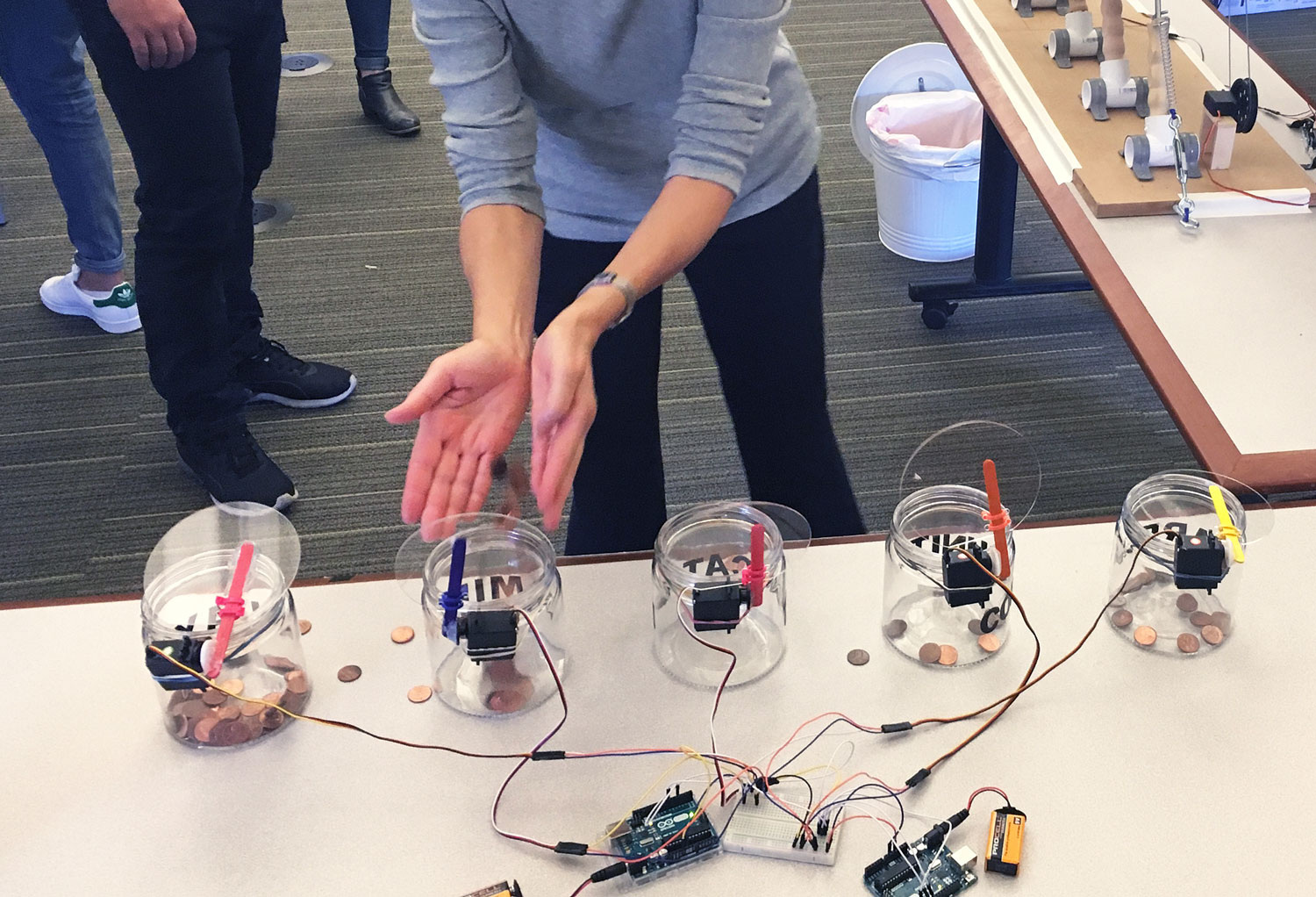

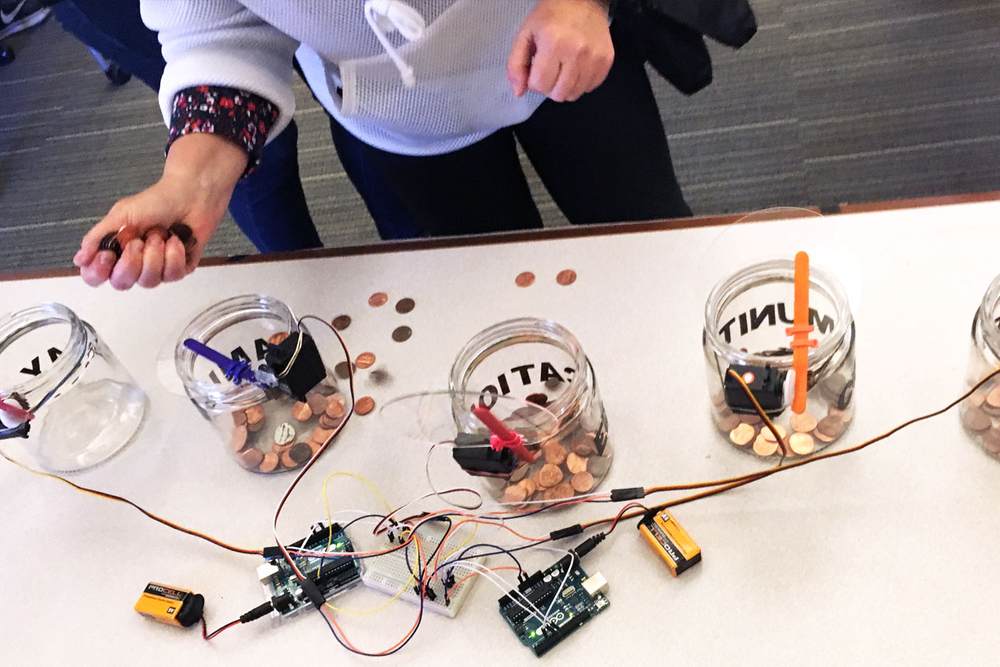

The participant’s lifetime is embodied in pennies, translating the average worldwide 71.5-year lifespan into 715 pennies. Over the course of 60 seconds, participants “spend” these pennies that represent their lifetime by allocating them into five different life target jars – Career, Community, Education, Family, and Play: these include servo-powered lids that open and close at random, adding a carnivalesque quality to the experience.

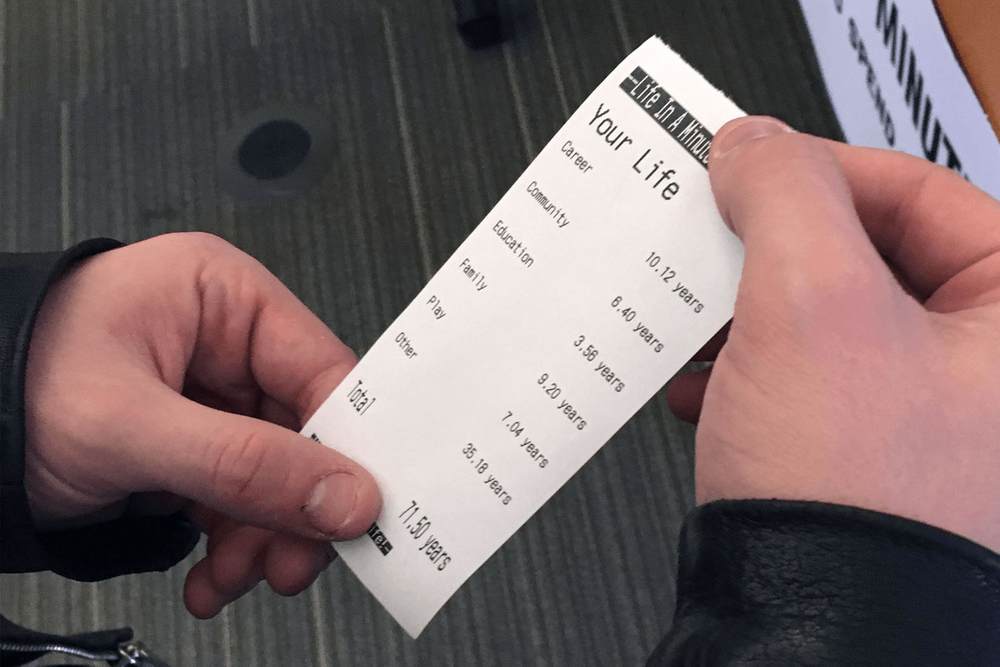

When time is up, players receive a receipt as evidence that embodies the “lifetime” spent and enables reflection after the experience has ended. The receipt is printed by an Arduino-powered thermal printer, with coin allocation weights mapped to years in a lifespan.

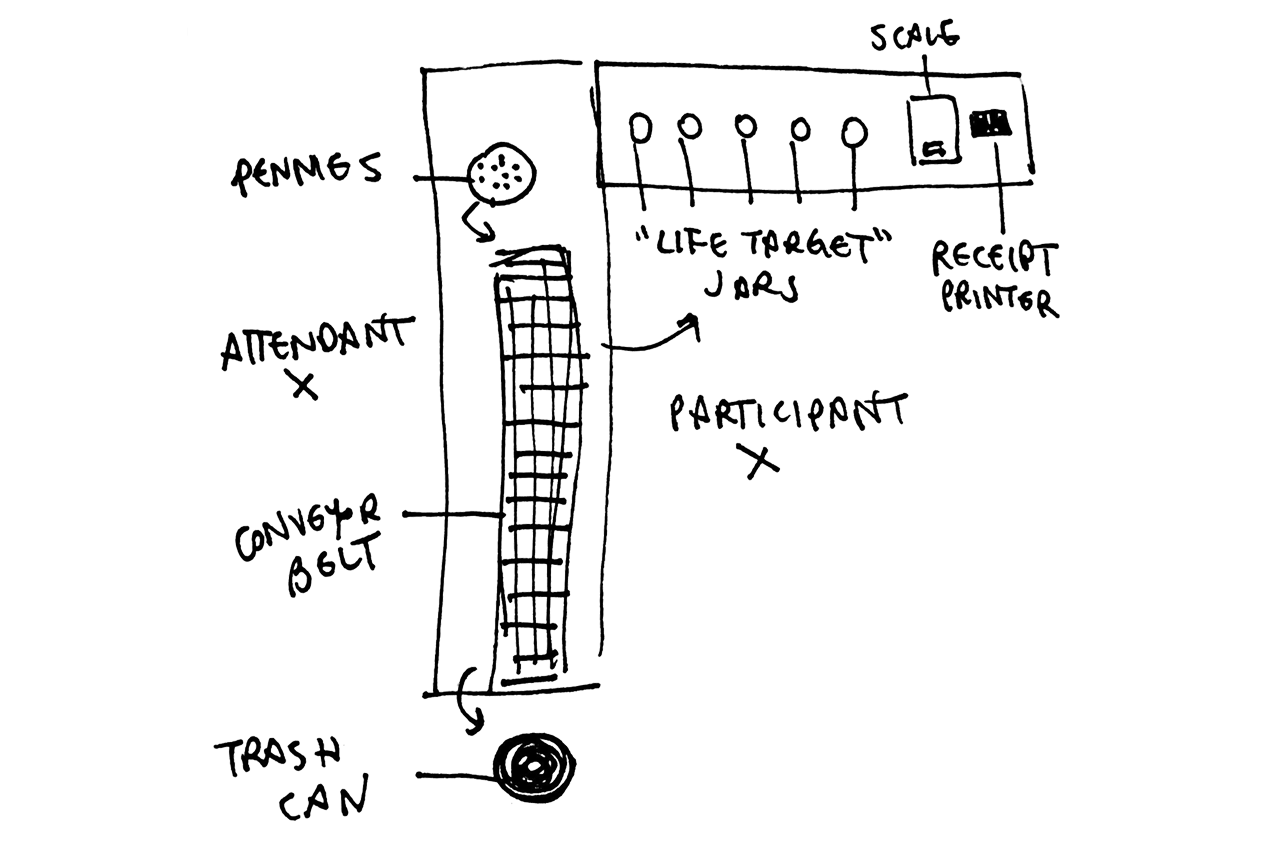

︎ Overview of the installation setup, including both the participant and an attendant.

︎An attendant deposits coins onto a conveyor belt for the participant.

︎The participant allocates coins picked up into jars of “life target” areas, whose servo-powered lids open and close at random.

︎When a minute has elapsed, each “life target” jar is weighed and recorded.

︎ Each participant receives a receipt of how they “spent” their time, with coin allocation weights mapped to years in a lifespan.

Outcomes

Rich feedback from 25 participants suggest the value of “Life in a Minute” as a cultural probe to uncover attitudes toward time scarcity and decision-making processes. For instance, some participants “spent” their coins as soon as they were dispensed; others waited at the end of the conveyor belt to collect as many coins as possible, delaying their time allocation. Another key contrast was in relation to the life target jars, opening and closing at random: some people waited for certain jars to open, while others allocated opportunistically to any jars available. Asking the participant about such behaviors afterward effectively sparked self-reflection and candid dialogue about their motivations, conscious or unconscious.

The game-like design of the interaction also layers in a sense of fun, occasionally inducing a competitive mindset. One participant remarked, “People with bigger hands have an advantage.” Another participant was observed peeking at another’s receipt, asking, “How did you do?” But the most unexpected method of engagement with the system involved pairs playing together, adding in a new layer of observable interaction. Among one duo, we overheard the following question, “What’s our strategy?” To which her partner replied, “To waste as little time as possible.” When asked why she chose not to play solo, another participant remarked, “Life is easier with a partner.”

︎ Exhibiting in the gallery of 2018 Ethnographic Praxis In Industry Conference.

︎ One visitor’s response to the project at EPIC.

Takeaways

Given the quality of such data, we propose that this work may be repurposed as a projective interviewing method. A key improvement would be to allow participants to self-identify categories of personally valuable “life targets,” as self-designated categories would downplay any prescriptive intention and permit greater interpretability for the participant. Additionally, the receipt or idealized “life summary” artifact could be compared to actual behavioral evidence, similar to Anderson et al.’s “ethno-mining” approach: for example, participants could be asked to map their real online behavioral data with broader “life targets.”

We offer “Life in a Minute” as a novel approach to understanding subjective perspectives about the value of time. By introducing an interactive installation, we open a space for thinking more broadly about new methods of collecting data which may more accurately mirror real sentiment and lived experiences.